10 Feb Foldable battery powered by bacteria from wastewater

Scientists have developed a bacteria-powered battery on a single piece of paper, which they say could be a cheap and easily manufactured power source for medical sensors in remote and developing areas.

The paper battery, which is foldable, is the latest example of what are known as bio-batteries, which store power generated by organic compounds. In this case, the power is generated by common bacteria found in wastewater.

The paper-based design is part of a new field of research called papertronics, which like the name suggests, is a fusion of paper and electronics.

The simple components needed to make these kinds of paper-based electronics should be easy to come by in remote parts of the world, which could make them a reliable backup in places where grid electricity or conventional batteries aren’t available.

“Papertronics have recently emerged as a simple and low-cost way to power disposable point-of-care diagnostic sensors,” says engineer Seokheun “Sean” Choi from Binghamton University.

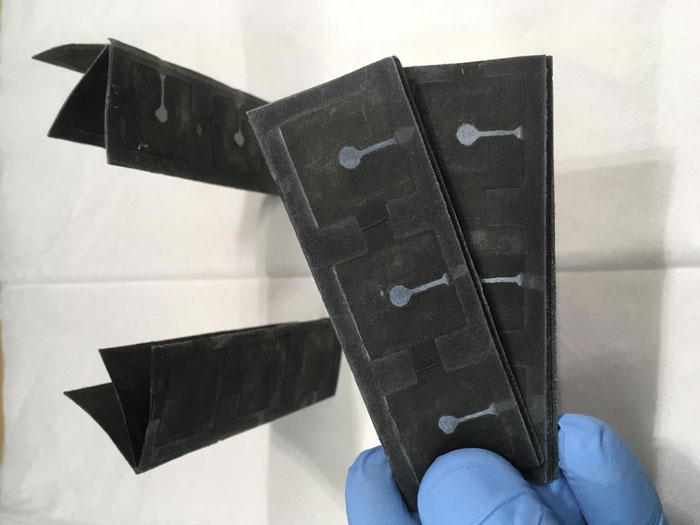

To make their battery, the researchers laid a ribbon of silver nitrate on a piece of chromatography paper. On top of this, they placed a thin layer of wax to create a cathode – the battery’s positive electrode.

On the other side of the paper, the team made a reservoir out of a conductive polymer, which acts an anode (negative electrode), once filled with a few drops of the bacteria-containing wastewater liquid.

When the paper is folded so that the cathode and anode come into contact, the battery is powered by the bacterial metabolism, also known as cellular respiration.

It’s not the first time researchers have experimented with malleable or unconventional battery designs.

Last year, a team from the US and China showed off an origami-style lithium-ion battery that incorporated ‘soft creases’ so that it can stretch and retract.

Months later, researchers in Sweden developed something called “power paper” – a sheet made of cellulose and polymer that’s able to store energy.

And just last month, scientists in the UK unveiled a battery design inspired by the human intestine.

Their lithium-sulphur battery emulates the finger-like protrusions in the human gut called villi, to resist degradation by catching sulphur fragments that break off over time.

In terms of the new paper battery, the amount of power output depends on how much paper you have and how it’s stacked and folded. As you can see in the image above, each foldable sheet of paper contains a number of the small, square-shaped batteries laid out in a grid.

In the researchers’ testing, they were able to generate 31.51 microwatts at 125.53 microamps with six batteries (three batteries in a row, folded onto another three), and 44.85 microwatts at 105.89 microamps in (six batteries, folded onto another three).

The researchers acknowledge that performance is variable depending on any misalignment of, or gaps between, the paper layers, and say a lot more work needs to be done to get more current out of the device.

Right now, it would take millions of the paper batteries to generate enough power for a 40-watt light bulb, so this kind of technology probably isn’t going to be a solution for powering conventional electronics any time soon.

But as it stands, the researchers say the battery is already powerful enough to run simple biosensors for things like monitoring glucose levels in diabetes patients or detecting pathogens in patients, which could help bring urgent medical aid to people who need assistance in places without electric power.

“Among many flexible and integrative paper-based batteries with a large upside, paper-based microbial fuel cell technology is arguably the most underdeveloped,” says Choi.

“We are excited about this because microorganisms can harvest electrical power from any type of biodegradable source, like wastewater, that is readily available. I believe this type of paper bio-battery can be a future power source for papertronics.”

The findings are reported in Advanced Materials Technologies.

This article originally appeard on : http://www.sciencealert.com